Pumping up the worthless with NFTs

By Mark Hurst • March 12, 2021

Mike Winkelmann is a 40-year-old digital artist living in Charleston, South Carolina. Better known as Beeple, he's arguably one of the most successful artists in history, given the price he commanded yesterday in an online auction run by Christie's. He sold one piece of art for $69 million. According to the New York Times, that puts Beeple third in line, after Jeff Koons and David Hockney, for the highest price ever paid for a living artist's work.

Beeple's artwork is a digital image, a compilation of drawings he's posted freely online for several years. This means that the buyer - whoever just paid $69 million for it - doesn't have possession of anything unique. In a sense, they don't own the artwork they just bought.

Now consider the Nyan Cat meme animation, which someone recently paid over half a million dollars for. But anyone can have the animation for free. In fact, I'll give you Nyan Cat right now. Click here for the animation, or see below for a still image:

The obvious question is how this common animation was worth half a million dollars. The answer draws on a tech term that I predict we'll soon tire of hearing about: "NFTs," or non-fungible tokens. An NFT is a tiny amount of identifying data associated with the object for sale, making that object unique.

In this case, the Nyan Cat animation is not unique - so in order to sell it, there has to be something attached that is unique, and near-impossible to duplicate. That's the role of the NFT: to serve as the unique data. You can think of it as a super-long password that would be impossible for anyone to guess. In this case, someone paid $580,000 and received the "password" associated with the Nyan Cat animation. (A proper technical description would involve the blockchain, which I'll avoid for now.) Anyway, with that "password," they now "own" Nyan Cat. More precisely, the owner is the person who holds the one single NFT for Nyan Cat, which gives them the bragging rights to say that they own Nyan Cat.

Pretty attractive sales pitch, right?

To be fair, we can draw a reasonably close analogy to the stock market. If I go online and buy one share of Apple, I don't really receive anything substantial in the transaction. I certainly don't get a physical slice of the company, like one square centimeter of their Cupertino headquarters building, or even a paper stock certificate. I'll just have a line in my online brokerage - physically, just some bits in a database somewhere - saying that I do, in fact, own one share of Apple.

The difference with the Nyan Cat NFT is that a share of Apple is backed by an actual company, that makes actual products, and earns actual money. (Of course, a ton of Apple's money comes from their usurious app store, and the surveillance revenue in Google's annual tribute to be the default iOS search engine, but let's leave that aside for now.) My point is that as insubstantial as a stock might be, there is at least some real-world value - call it "intrinsic value" - backing the stock.

An NFT purchase, though, has nothing substantial about it. In the Nyan Cat sale, there was no intrinsic value backing the transaction. Far from any attempt to hide the lack of worth, the transaction puts the absurdity on full display: "We're selling a meme for a half-million dollars! And not just any meme, but the silly cat animation that's been around for years!"

The only possible value here comes from a "greater fool" scheme, in which you buy an overvalued asset - it's a "foolish" purchase - in the hopes that you'll find someone who is a greater fool, meaning they'll pay even more. This is a classic tulip-mania type of bubble, which richly rewards the insiders who get out early, and punishes the saps who are left holding the bag at the end. If this sounds familiar, I wrote about it in Venture capital and the WeWork con job (Dec 3, 2020). Silicon Valley VCs are getting better and better at running the scam.

Now Silicon Valley sees the possibility to use NFTs - built with trendy, magical-sounding terms like blockchain and cryptocurrency - to pump up bubbles on anything digital, no matter how worthless. Maybe especially if it's worthless. Venture capitalist Ben Horowitz, who has a stake in NFT marketplaces, put this spin on the purchase of worthless assets: "You're buying a feeling." (Note that he doesn't specify which feeling. My money's on "regret.")

Where this all takes us, possibly, is an environment where intrinsic value, any inherent substance, is actually devalued. Much like manual labor is devalued in the knowledge economy, NFTs could inaugurate an economy where everything is for sale, and something makes money as long as it's (a) worth nothing, and (b) backed by enough attention to pump up the auction price.

Explaining the scheme

Here's how the scheme works. First, we start with something that's worth nothing. This is important, since if it was worth anything at all, the intrinsic value would set a limit on the auction price. (One share of Apple would never zoom up to a half-million dollars, but an endlessly copied cat animation - since everyone knows it's worth nothing - well, why not?) Perhaps I'll start an auction to sell a new word I just came up with: "blandlebroomenzappyfinagle." I checked, and no one has ever come up with this before. It's mine. Sure, you can copy it - in fact, by reading this column you already have a copy - but I'll assign the NFT and open the auction.

Second, we need to direct attention to our worthless NFT, because doing so transmutes it into gold. Here we see that NFTs are less like the stock market and more like the bane of our collective existence over the past decade or so: social media. Think of the all-too-common occurrence when social media takes a worthless idea, usually a lie of some sort, and elevates it - imbues it with momentum and engagement - thereby endowing the idea with the power to wreak real-world harm. NFTs act in a similar way, taking something worthless and giving it, at least temporarily, real-world monetary value.

Remember Beeple, the artist I mentioned above? His drawings are fine, but they're not worth tens of millions of dollars. The key is his following on Instagram, nearly two million strong. His NFT-enabled digital artwork was purchased for $69 million not because of any intrinsic worth but because of the attention he commands on social media.

It should be obvious who benefits the most from NFTs: the owners of social media companies, which control the attention market. That's why it's no surprise, at all, that Jack Dorsey is selling his first tweet as an NFT. The asset itself is totally worthless - here it is, you can have it for free - but the attention Dorsey is lavishing on the NFT pumps up the price. The current bid is over $2 million. Dorsey says this first sale will go toward charity. But if this helps NFTs take off, Dorsey's position as social media CEO - much like that of Mark Zuckerberg, and the Silicon Valley VCs running the scheme - will become much, much more powerful.

The worthless gets pumped up, and the worthwhile gets devalued. What a world.

(See also perspectives by David Strom and Ian Bogost, who notes that "the dumbest possible ideas always win.")

A T-shirt that's real

Speaking of substantial assets, my WFMU show Techtonic has a new t-shirt, for donors to the station's pledge drive going on now. The shirt features my weekly signoff, which has become a kind of clarion call for listeners:

Click here to get the T-shirt: Pledge $75 one-time, or $10/month, and BE SURE TO check "1 DJ Premium." The t-shirt is on the next page, in the Monday section.

Credit for the T-shirt design goes to London-based designer Jethro Haynes.

Updates

1. A couple of weeks back I wrote about Bitcoin, the Arctic, and climate change, in Tech warnings from unlikely sources. A NYT article this week, Bitcoin's Climate Problem, quotes one scientific journal calling Bitcoin a "largely gambling-driven source of carbon emissions." Sounds about right.

2. Last week I wrote How not to fix customer service, which described the spectacular failure of Citibank's internal Flexcube platform. I offered a guess at a diagnosis, writing that "I imagine that Flexcube wasn't the only financial software tool Citi could have licensed, but Flexcube might have been the low bidder."

Felix Salmon, chief financial correspondent at Axios and past Techtonic guest, helpfully wrote in with this correction:

Agreed that the Flexcube UI was atrocious, but disagreed on the reasons why.

Two big things are going on here. One is bank mergers, which Citi (a/k/a Travelers Salomon Smith Barney) has done a lot of. All those legacy banks come with legacy tech, and it's basically impossible to merge it all into one state-of-the-art system. So everything gets duct-taped together in a way that makes it impossible to change anything because if you try, everything else will break.

A prime example: Audible has a *terrible* UI and *terrible* tech. You can't use an Amazon credit to buy an Audible audiobook, for instance, which is insane, given that Amazon owns Audible. And Amazon is a tech company! But even Amazon can't work out how to integrate Audible's legacy tech into something more modern, or how to update it without breaking everything.

The other thing is that the Flexcube software *wasn't designed* to do what it was being asked to do in this situation. This was a horrible kludge and was known to be a horrible kludge. If you want to pay off one creditor without paying off everybody else, you should just do that! But Citi's systems couldn't make that work, so instead they had to use Flexcube + wash account etc with all the consequences we know about.

So yes, the Flexcube UI is terrible. But it might well have been great when it was designed, and when it was used for what it was designed to be used for.

Thanks to Felix for the clarification. Legacy tech is kludgey enough, and when we try to integrate it into another legacy system, it gets even more broken.

Mandatory fun item

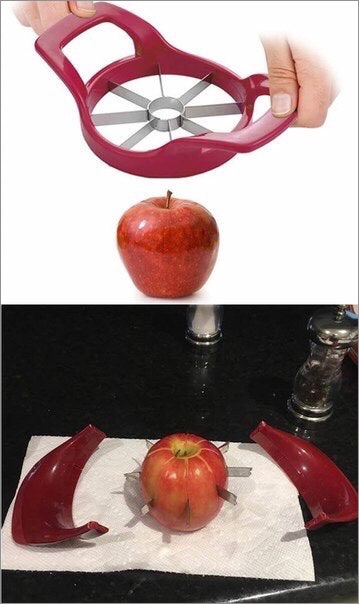

Speaking of, sometimes I wish I still ran my old site This Is Broken - like when I come across images like this:

That's about it for today. If you're new here, read past columns. (You can also get them via the email newsletter.) And please do pledge to Techtonic to get that T-shirt.

Until next time,

- Mark Hurst

Email: mark@creativegood.com

Read my non-toxic tech reviews at Good Reports

Listen to my podcast/radio show: techtonic.fm

Subscribe to my email newsletter

Sign up for my to-do list with privacy built in, Good Todo

Twitter: @markhurst

- - -