How not to fix customer service

By Mark Hurst • March 4, 2021

One of my favorite stories about customers involves a company that Creative Good advised a few years ago. The client was a major company that made a certain product used in a business setting. To keep things anonymous, let's call it a spatula. Actually, let's call it a networked spatula: this was a product with lots of built-in features for sending and receiving data, designed for use in offices across the country.

Needless to say, as these things usually go, the networked spatula wasn't particularly well designed. The features were presented in a complicated user interface. The user guide, which most users didn't want to read anyway, was poorly written. When we interviewed users, they described how they disliked, even hated, this tool - but were forced to use it because it was the only spatula in the office for flipping those particular pancakes.

All of this meant that users eventually had to contact Spatula, Inc. customer service for help in getting through their tasks. Online guides and FAQs were just as poorly designed as the tool, so users eventually called the phone number printed on the spatula: "For help, call 1-800-SPATULA." The phone call subjected the users to yet more frustration, as they had to wait several minutes before an overworked and underpaid call-center agent wearily got on the line.

My team and I had a bird's-eye view of everyone involved: the product team responsible for the spatula, the users forced to muddle through its disappointing UX, the call center employees endlessly answering the same questions, and the executives trying their best to improve the numbers on their spatula business. It was that final constituency, the leadership, where the story turned legendary.

Leadership at Spatula, Inc. was interested in quantitative measurement. Of everything. Certainly revenue, costs, units sold, that sort of thing were all scrutinized - but it was more than that. Leadership wanted to quantify the customer experience - ideally, with one number that would embody the totality of how the product was performing with customers. I'm fairly sure this company said the usual platitudes about customers being their "most important asset" and that sort of thing. But what they were actually concerned about were the numbers.

After some discussion (which my team was not a part of), leadership finally decided that of all the indicators and evidence, they would singularly focus on the number of calls coming into the call center. After all, customers kept calling with complaints about their spatulas - and those calls were expensive! - so if the calls went down, that would mean both that fewer customers were complaining, and that the company would pay less in call-center costs.

Thus was born a new strategy that informed the next version of the spatula. Reduce incoming calls. The product team, under extreme pressure from the executives, found a way to achieve the strategic goal. In a way, it was almost a silver-bullet solution to the quandary: it was inexpensive and easy to implement, and the results were immediate.

Perhaps you've guessed what Spatula, Inc. did to carry out its soaring strategic vision. The next version of the spatula, when it was mailed out to customers a few months later, bore with it one small change. The call-center phone number, which previously had been printed directly onto the spatula, had been removed.

You'll never guess what happened next: the number of calls coming into the call center went down! Leadership, at last, got the quantifiable proof they were looking for. Users, of course, weren't happy - they made that clear in our user research, conducted soon after the phone number disappeared - but that wasn't a quantified measurement that concerned leadership. The final Creative Good presentation - emphasizing qualitative things like listening, and empathy, went mostly unheeded.

Citi learns that what's not a number still counts

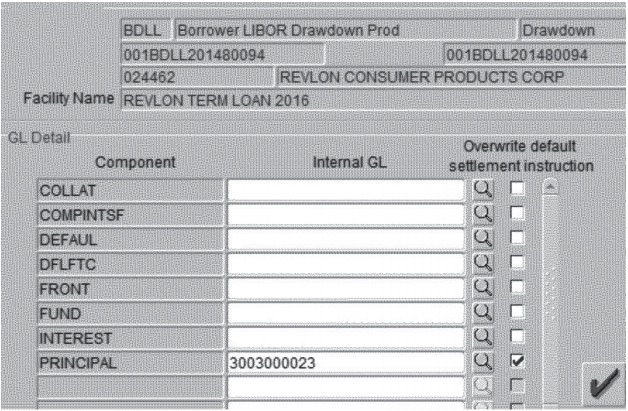

I couldn't help but think of spatulas when I saw the recent news about Citibank. As reported in Ars Technica and Bloomberg, the company suffered a $500 million dollar loss due to terrible UI design. Specifically, a Citibank subcontractor made a mistake while entering data on this screen...

...which ended up accidentally sending almost a billion dollars to Citi's creditors, rather than the intended $7.8 million. Ouch. (Citi lost its court case, too.)

Certainly one lesson we can draw here is that UI design really does matter. The UI shown above, from a software tool called Flexcube, was probably thrown together as quickly as possible in order to minimize any extra costs like UI design. Of course, a screen like that could have been better designed for a negligible investment. But anyone who's spent time in enterprise software knows that clunky and confusing UI design is more common than not.

More pertinent to our story today, the Citibank experience matches that of the spatula company, in that leadership was narrowly focused on some quantitative measure, rather than simply creating a tool that worked well for the user. I imagine that Flexcube wasn't the only financial software tool Citi could have licensed, but Flexcube might have been the low bidder. In addition, Citi know it could further minimize costs by off-shoring the data entry - not unlike the overworked, underpaid reps at the Spatula, Inc. call center.

I always told clients that the best customer service strategy is to create a good product in the first place: the better the product, the fewer users will be contacting customer service for help. But that's not an easily quantifiable strategy, at least in the short term. Many companies prefer to optimize for some narrowly defined short-term metric - even if that means taking the phone number off the spatulas.

The lesson Citi should learn from this debacle is what Spatula, Inc. never did learn: the most important aspect in building a product, or a community, or a customer base, isn't quantifiable. Building something that's genuinely helpful should of course make use of the quantitative, but it will never succeed if it's exclusively devoted to a number. Maybe it could be said like this: You can't count the things that count the most.

Mandatory fun item

A very different sort of UX review comes from McSweeney's: The UX on this small child is terrible (by Leslie Ylinen, who is no stranger to toddler humor). My favorite is the comment about "journey mapping":

There are just so many pain points creating an unsatisfactory user journey. The child goes limp when you try to lift it. It goes stiff when you try to change the clothes. It poops after it gets into the bathtub, but before it reaches the toilet. The tone and voice lack consistency, jolting from jubilant to irate in just a few clicks. This Small Child won't open its mouth for a toothbrush, but won't close it during my cousin's wedding ceremony. It's as if this Small Child was not designed with accessibility in mind.

Speaking of listening to customers: I'm considering creating a online course on customer experience - discussing user research, product strategy, and some of the case studies in Customers Included. Feedback/suggestions? Email me.

And that's about it for today. If you're new here, read past columns. (You can also get them via the email newsletter.)

Until next time,

- Mark Hurst

Read my non-toxic tech reviews at Good Reports

Listen to my podcast/radio show: techtonic.fm

Subscribe to my email newsletter

Sign up for my to-do list with privacy built in, Good Todo

Email: mark@creativegood.com

Twitter: @markhurst

- - -