Why you should pay attention to ‘Made in China’

By Mark Hurst • June 11, 2021

“This is the saddest Techtonic yet,” one of my listeners commented during my show this week, but “I’m glad this conversation is being aired.” Similarly, today’s column bears a difficult message but I’m glad to be able to share it with you.

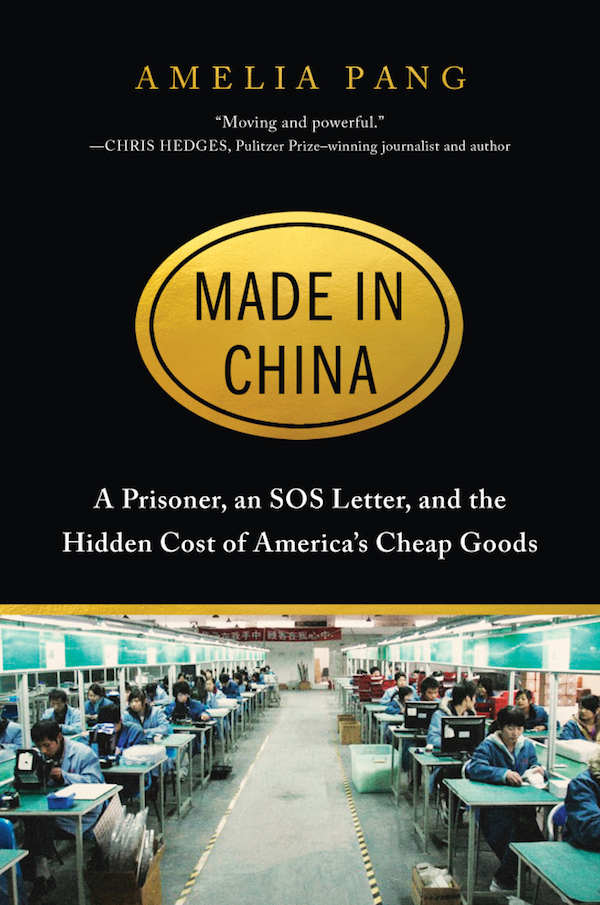

My show this week focused on Made in China: A Prisoner, an SOS Letter, and the Hidden Cost of America’s Cheap Goods, a book by Amelia Pang about the widespread use of forced labor in Chinese manufacturing for American products. The SOS letter in the subtitle refers to an incident in 2012 when a suburban mom near Portland, Oregon opened a box of Halloween decorations that had been purchased at Kmart. The box of decorative gravestones contained a handwritten note by a forced laborer describing the inhuman conditions at the facility where the decorations were made.

As the book unrolls the story of the SOS letter – who wrote it, how they managed to slip the note into the box, and what happened next – the book covers the larger issue of forced labor in China. It's a widespread practice across multiple industries: among suppliers of Apple and other tech companies, in the cotton industry of Xinjiang, and in the hundreds or thousands of facilities making cheap decorations and knickknacks to be sold in big-box stores and on Amazon.

While forced labor represents a small slice of Chinese manufacturing, the raw numbers are daunting. Just in the western region of Xinjiang, there’s an estimated million or more people – chiefly drawn from the native population of Uyghur Muslims – detained in re-education camps, many of which include manufacturing. But it’s not limited to Xinjiang Uyghurs. Throughout China, citizens from various groups – including political dissidents, religious minorities (non-state-sanctioned Christians, Falun Gong adherents, as well as Uyghur Muslims), and human-rights lawyers who defend them – have all disappeared into the prison system, usually without any sort of trial or legal proceeding. Once they arrive at a detention facility or re-education camp, they are often put to work manufacturing goods for American companies.

It’s important to acknowledge the role played by the US in this system, and to avoid a throwaway conclusion: “Well, that’s China for you.” As though the CCP (Chinese Communist Party) is the only bad actor. Remember that the forced laborers are creating products for purchase by American consumers. Pang’s book lists some of the brands and companies that reportedly draw on Chinese forced labor: Apple, Nike, BMW, Volkswagen, Muji, and Uniqlo, among many others. As Pang writes, this is “more than a story about Chinese human rights. [It’s] about unfettered globalization and overconsumption.”

The difficult truth at the heart of Pang’s book, if we are willing to face up to it, is that we’re all complicit in this system. The CCP plays a part, for sure, but so do well-known brands – which are, themselves, pushing their supply chain to extreme measures in order to deliver products to us, the customers, at rock-bottom prices. Forced laborers, after all, produce work at a high rate (prisoners work 15 to 20 hours a day, under threat of torture), at almost zero cost.

A shiny Apple can still be rotten

I was interested to see the recent media coverage of the WWDC, Apple’s annual infomercial in which they feed journalists the list of shiny new features that are coming soon to iPhones and MacBooks. How many articles did we see, dutifully listing the bullet points from Apple’s advertising, talking about new screen gestures, and innovative image-to-text features? The fawning coverage was very different from a story in The Information on May 10 that got just a blip of attention: Seven Apple Suppliers Accused of Using Forced Labor From Xinjiang. Wayne Ma writes:

The Information and human rights groups have found seven companies supplying device components, coatings and assembly services to Apple that are linked to alleged forced labor involving Uyghurs and other oppressed minorities in China. At least five of those companies received thousands of Uyghur and other minority workers at specific factory sites or subsidiaries that did work for Apple, the investigation found. The revelation stands in contrast to Apple’s assertions over the past year that it hasn’t found evidence of forced labor in its supply chain.

Once again Apple appears to be a little less than truthful, as I’ve written recently (1, 2). Asserting “no evidence of forced labor” requires willful ignorance, at best, given Apple’s deep, years-long dependency on Chinese labor for its manufacturing. Apple’s statement is contradicted by Amelia Pang herself, who traveled to China for book research and posed as a buyer at a forced-labor camp. She followed a truck of manufactured goods leaving the facility, down the highway, all the way to its arrival at an official Apple supplier listed on Apple’s website. (Pang describes the experience during our Techtonic interview.)

I realize that, in bringing up Apple’s misbehavior again, I’m continuing to offer some very unpopular findings about a very popular company. What’s worse, I’m suggesting our complicity – yours and mine both – in maintaining and encouraging a system that has locked up, most likely, several million Chinese citizens, without judicial due process, in slave-labor conditions, in order to produce the computers, clothing, and Christmas decorations that we demand – we demand! – to sort by price, and buy with a click.

It’s a nightmare, in other words. And it deserves some sort of response.

Common reactions

From reading comments online, I know it’s tempting to write off the problem of forced labor as something imaginary, or impossible, and at any rate worth ignoring. Here are a few common reactions I’ve seen:

• “Why are you ‘othering’ China? Don’t be xenophobic, stick to the US’s problems.”

• “There’s forced labor in American prisons, too, you know.”

• “The reports must be exaggerated, maybe part of an American propaganda effort to spread anti-China stories.”

• “There’s no solution anyway. What do you want us to do, visit every single manufacturing facility in China and sit with each worker to make sure they’re not mistreated?”

• “Why should I even care about this? There are lots of other problems in the world, and one person can’t make a difference anyway.”

I’ll grant that each of these has a grain of truth. It can be tempting to point the finger only at the CCP, in a sort of nationalist way, and ignore our own behavior; there is certainly forced labor (and emerging tech-amplified financial exploitation) targeting American prisoners; anti-China propaganda does exist and makes some of the same points; a magic-bullet solution does not exist; and the world is, regrettably, full of intractable problems – as well as TV shows and social media offering distractions from those problems. Having said that, I come right back to my point. None of those reactions qualify as a reason to ignore the nightmare. It remains, staring us in the face.

“Then what should we do?” I’m not sure. I’m not selling a partisan policy or ideology, but instead suggesting this: pay attention. Whatever long-term solutions might be possible, they all start with this first step. Don’t look away, don’t retreat into a distraction. Just pay attention.

If you want to take a further step of reading just a bit more, I posted a bunch of links on the playlist page of Monday’s show (scroll down to the “Links” section). One article in particular I’d recommend is a New Yorker story from the April 12, 2021 issue: Surviving the Crackdown in Xinjiang, by Raffi Khatchadourian. While it focuses on the re-education camps where an estimated million Uyghurs have been sent, the article also gives some helpful context around the forced-labor system that Pang writes about in her book.

I couldn’t shake a thought as I read that New Yorker story. In 1945, when the Allies liberated Hitler’s concentration camps, everyone said, “never again.” We'd never allow any country, anywhere, ever again, to construct a system of camps to erase a minority. And here we are today, faced with the nightmare, reappeared, grinning death as we swipe the screen to distract ourselves. The difference, this time, is that the camps are helping keep our iPhone prices down.

Listen to my Techtonic interview with Amelia Pang, about Made in China

Become a Creative Good member to support this email newsletter

Comment on this column: Creative Good members, post a comment on the Creative Good Forum. If you're not a Creative Good member, read the official announcement and join us!

Until next time,

-mark

Mark Hurst, founder, Creative Good – see official announcement and join as a member

Email: mark@creativegood.com

Read my non-toxic tech reviews at Good Reports (see the new entry on Removing your info from data brokers)

Listen to my podcast/radio show: techtonic.fm

Subscribe to my email newsletter

Sign up for my to-do list with privacy built in, Good Todo

Twitter: @markhurst

- – -