The Luddites warned us about Google

By Mark Hurst • October 25, 2023

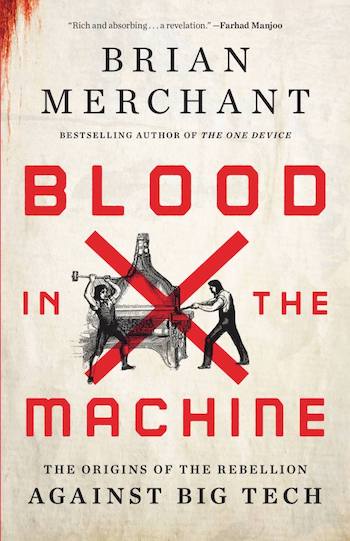

I was happy to speak recently on Techtonic with Brian Merchant about his book on the Luddites, “Blood in the Machine: The Origins of the Rebellion Against Big Tech.” As the Los Angeles Times’ technology columnist, Merchant might seem to be an unlikely promoter of 19th-century English textile workers who smashed factory machines. After all (so goes a popular trope), weren’t the Luddites anti-technology?

The reality, as Merchant explains in his book, is that the Luddites were not against technology at all. They weren’t backwards, unenlightened, or reactionary. To the contrary, they were canny and accurate critics of factory exploitation, an emergent business model in 1810s England. New automated tools like the power loom prompted factory bosses to fire their most skilled workers – throwing them and their families into poverty – while replacing them with vulnerable and exploitable workers. Many of these were children, some as young as seven years old, taken from orphanages and transported on trains to factories, where they were mistreated, maimed, or killed.

The Luddites correctly identified factory automation as a fatal threat. Without any meaningful social safety net or job retraining, the factory system meant starvation for them and their families. When their repeated appeals to Parliament had no effect, they moved to their next option: “frame breaking,” or destroying the machines that represented the new economy.

Here’s something I hadn’t understood before I read Merchant’s book. When the Luddites entered a factory, usually late at night, to destroy machines, they didn’t start indiscriminately smashing everything in sight. Instead, they identified just those machines that used unskilled labor (often children) to turn out low-quality products. It was the exploitative technology that got smashed by sledgehammers. The other machines, those used by skilled laborers, were left untouched.

Although the Luddites were eventually crushed by the state, their legacy lives on. So do the problems they faced. Our Big Tech-dominated economy is strikingly similar to England’s two hundred years ago. As Brian Merchant writes in a recent Washington Post op-ed (Sep 18, 2023):

Sadly, the Luddites’ plight is as relevant as ever. The parallels to the modern day are everywhere.

In the 1800s, entrepreneurs used technology to justify imposing a new mode of work: the factory system. In the 2000s, CEOs used technology to justify imposing a new mode of work: algorithmically organized gig labor, in which pay is lower and protections scarce. In the 1800s, hosiers and factory owners used automation less to overtly replace workers than to deskill them and drive down their wages. Digital media bosses, call center operators and studio executives are using AI in much the same way.

The source of the troubles, then as now, is the concentration of money and power. Big Tech companies monopolize markets, skirt regulations, and deceive consumers with low-quality products, all while exploiting labor (whether gig workers in the US or third-party contractors in less wealthy countries). 19th-century English factory owners did all of this first and thus were the “original tech titans,” writes Merchant. Their grasp for power was no different from what we see today in Silicon Valley.

What is different is the response. Unlike Parliament in the 1810s, which was fully aligned with the factory owners, today we’re seeing some government action to rein in the worst actors. A good example is the Google antitrust trial. In this hugely important case – which is getting strangely little coverage in the press – the Department of Justice is showing how Google’s search quality has declined, even as Google has used its monopoly position to squelch any hint of innovation or improvement from competitors.

Get Mark Hurst’s weekly writings in email: Subscribe. (Or join Creative Good.)

Sign up for this newsletter.

One important detail from the trial emerged this week. As reported by the Federalist (Oct 24, 2023), “Google pays around $19 billion annually to Apple to ensure that Google is the default search engine on all Apple handsets.” While it’s an example of Apple’s hypocrisy – claiming to deliver privacy while selling out users to Google – this is really a key point in the DOJ’s case. If Google is popular merely because (as it argues) it creates the best user experience, why does Google need to pay Apple $19 billion a year to remain the iPhone default?

The Luddites warned us about Google. Too much power in too few hands leads to bad outcomes for everyone: first for workers, then for customers, then for the industry itself. This is the essence of Cory Doctorow’s point about “enshittification,” which we discussed in our March 2023 Techtonic interview. As Cory wrote in January:

Here is how platforms die: first, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die.

Google is far along in its descent. As Doctorow posted a few months ago:

Google Search suuuuucks.

It sucks in so many ways. Search results are cluttered with poorly denoted ads from businesses whose websites aren’t good enough to warrant inclusion at the top of the listings on their own merits. The websites that do float “organically” to the top of the listings are often spammy garbage, filled with algorithm-pleasing nonsense.

The grasp for power makes people do bad things.

A good counterexample to Google’s unethical dealings is the life of Charles “Chuck” Feeney, who passed away earlier this month. As founder of Duty Free Shops, Feeney made hundreds of millions of dollars before deciding, in middle age, that he didn’t want a life of extreme wealth. He gave away nearly 100% of his money, leaving himself just enough to live in a small apartment with his wife. I read his biography a few years ago, and one passage has stayed with me ever since. Feeney was explaining why he decided to abandon his wealth. He said that after he became rich, he gradually realized that he was surrounded by people who were lying to him. He couldn’t stand the deception brought about by that much money. (Read more in Feeney’s NYT obit – and WSJ obit.)

The Luddites were right. The concentration of money and power is a perverting force. Google’s corruption exemplifies the problem. Chuck Feeney, like the Luddites, showed a way out. I’ll join Brian Merchant in saying: I’m a Luddite. You should be one, too.

• Stream my Techtonic interview with Brian Merchant

• Episode page with links and listener comments

• More Techtonic episodes at techtonic.fm

Announcing a new 25% discount

The Creative Good Forum has an entire thread devoted to Google’s antitrust trial – with news, analysis, and commentary. Join Creative Good and get access to this and more (like the new thread, just posted, about Facebook’s lawsuit from over 40 states). The Forum is a uniquely useful resource, allowing you to keep track of tech developments – from antitrust trials to generative AI news – in one place.

To celebrate 25 years of the Creative Good newsletter, I’m announcing a 25% discount to Creative Good membership. This is a limited-time offer, so sign up soon. The more members there are in the Creative Good community, the better this resource will become for all of us. Join Creative Good with a 25% discount.

Hope to see you on the Forum.

-mark

Get Mark Hurst’s weekly writings in email: Subscribe. (Or join Creative Good.)

Sign up for this newsletter.

Mark Hurst, founder, Creative Good – see our services or join as a member

Email: mark@creativegood.com

Listen to my podcast/radio show: techtonic.fm

Subscribe to my email newsletter

Sign up for my to-do list with privacy built in, Good Todo

On Mastodon: @markhurst@mastodon.social

- – -