ChatGPT’s dangers are starting to show

By Mark Hurst • March 17, 2023

Earlier this week I watched OpenAI’s demo of GPT-4, the latest version of the popular chat bot. The model is definitely getting more flexible and powerful, taking on new sorts of challenges:

• reading the tax code and calculating tax liability

• interpreting an image of a squirrel holding a camera to say why it’s funny

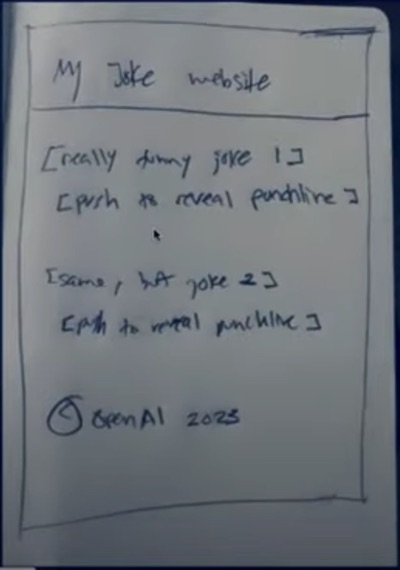

• scanning a hand-drawn (on paper) sketch of a web page, then creating a working model of it in HTML and Javascript

Assuming these were all carried out by ChatGPT without behind-the-scenes trickery, it’s an impressive feat. That sketch-to-working-website function – again, assuming OpenAI is telling the truth in its claims – is especially surprising. Below is the sketch shown in the demo:

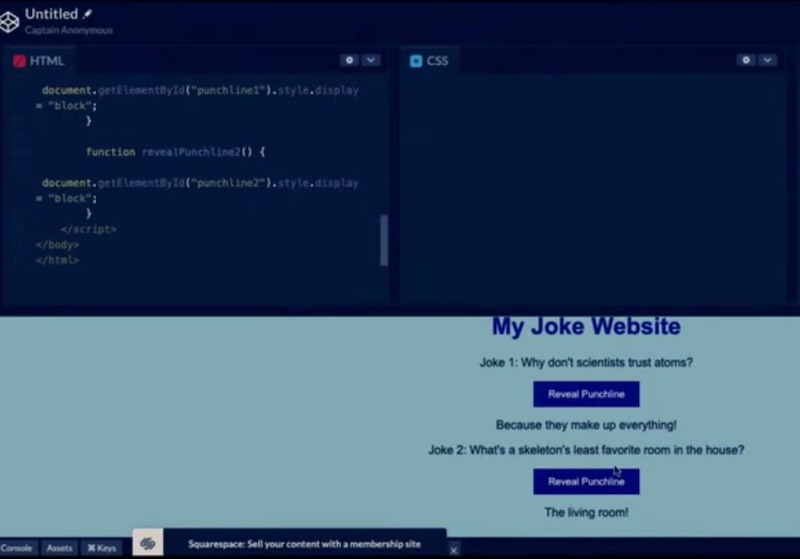

And below is the working webpage with clickable buttons revealing the punchlines of the jokes:

OpenAI’s close partner Microsoft has announced that it’s integrating ChatGPT into Office, in a new feature called Copilot (sources: 1, 2) – what might better be called “the revenge of Clippy.” (Just when you thought it was safe to open a Word doc... he’s baaaaack!) Call me cynical, but this is just slathering another user interface layer onto the disappointment that is the Office suite. Tools built ground-up for one purpose, like ChatGPT, might be good in their narrow contexts – as in the demo above – but things are different when you take a decades-old code base and apply a thick layer of UI glop on top of it. Expect to hear complaints from Office users, soon, about how AI is turning Word, PowerPoint, and Excel into even more frustrating experiences.

Missing the “why”

The search for the use case of ChatGPT continues. As I wrote in Where are the customers’ chats? (Feb 24), the tech media is repeating the claims of Microsoft and OpenAI without digging into the fundamental question: what good are chat bots and other AI tools? I know they can write limericks and term papers, and offer some simple coding answers. But I mean as a category of technology, are they addressing some pain point – or are they (admittedly) impressive statistical engines looking for some reason to exist?

Over at the Creative Good Forum we’ve been discussing ChatGPT (and this is one reason I value the Forum and think you would, too: because people are posting, and discussing, different perspectives on tech developments). Anyway, on the Forum, Creative Good member P. pointed out a use case for ChatGPT that actually is better than using a search engine: identifying constellations. Take a photo of a given jumble of stars, and try feeding that image into a search engine to identify. It’s unlikely to give the right answer – and maybe won’t get any answer at all. On the other hand, if it works as claimed, GPT-4 presumably could identify the constellation easily from that photo.

That’s not the end of the task, though. As with any chat bot output, we have to allow for the possibility that the answer is wrong. We need to find out whether this is really that constellation. And that’s where a search engine is helpful, in a validation step. For example, running a search (on Duck Duck Go or elsewhere) for the name of the constellation would bring up an image that could then be compared with the original photo.

So: tools like ChatGPT could, in some cases, be used to create a tentative answer, after which a search engine – or, for that matter, a human expert – can be used for validation or error correction.

This gives a possible answer to the “why” question: a chat bot could be superior to a search engine, if it’s a kind of question that a search engine couldn’t easily answer, and there’s an easy way to validate the chat bot’s answer with some other resource.

Get Mark Hurst’s weekly writings in email: Subscribe. (Or join the CG Forum.)

Sign up for this newsletter.

Lurking dangers

All of this comes with a caveat: this usage of a chat bot is most appropriate when it’s OK to generate a tentative answer, when you have the time to go through a validation step, and when there are no particular harms in having the wrong answer generated in the first place. Identifying a constellation with a chat bot seems pretty benign. There are other questions, though, that are especially important to avoid giving wrong answers for.

Cartoonist Ted Rall writes about one such problem. In ChatGPT Libeled Me. Can I Sue? (WSJ, March 16, 2023), Rall recounts his experience asking ChatGPT about a longtime friend.

I asked: “What is Scott Stantis’s relationship to Ted Rall?” After correctly identifying us both as editorial cartoonists, ChatGPT described our relationship as “contentious” and “complicated” and elaborated: “In 2002, Stantis accused Rall of plagiarism after Rall used a similar idea and composition in one of his cartoons as Stantis had used in a previous cartoon. Rall denied the accusation and claimed that the similarity was coincidental. The controversy led to a public feud between the two cartoonists, with each accusing the other of unprofessional conduct.”

None of this is true.

ChatGPT had totally made up – or, to use the trending term, “hallucinated” – both the feud and the plagiarism charge. Here we see a risk of ChatGPT, sorely underreported by tech journalists mesmerized by the shiny new tool, that the chat bot presents itself as an authority while delivering outrageous falsehoods.

Once again, we’ve discussed this on the Forum. Creative Good member S. posted an example in which ChatGPT delivered the wrong answer on a particular question. After S. noted the mistake, ChatGPT apologized, then generated another wrong answer. Once again S. pointed out the mistake, and ChatGPT apologized again, proceeding to generate... the original wrong answer from its first response.

The chat bot, in other words, has the capability of being “confidently wrong,” and continuing to be wrong, even when prompted to fix the error.

Get Mark Hurst’s weekly writings in email: Subscribe. (Or join the CG Forum.)

Sign up for this newsletter.

What does the billion-dollar bot have to say for itself? Ted Rall asked ChatGPT about its liability for issuing libelous statements. Here’s what it said:

As an AI language model, I cannot say anything defamatory about you, as I am programmed to provide objective and factual responses.

In other words, “Good luck suing me. I’m just a disembodied algorithm acting as a Play-Doh extruder.”

This reveals a particularly insidious possibility: Microsoft launches ChatGPT – in Office, in Bing, elsewhere – allowing it to give answers to thousands, millions, billions of questions. Microsoft and OpenAI reap massive gains as a result. But some percentage of those interactions give wrong answers, and people are harmed, sickened, or even killed. Microsoft brushes off the complaints, claiming that “It’s not our fault what the chat bot decides to say. Heck, we don’t even understand how it works!”

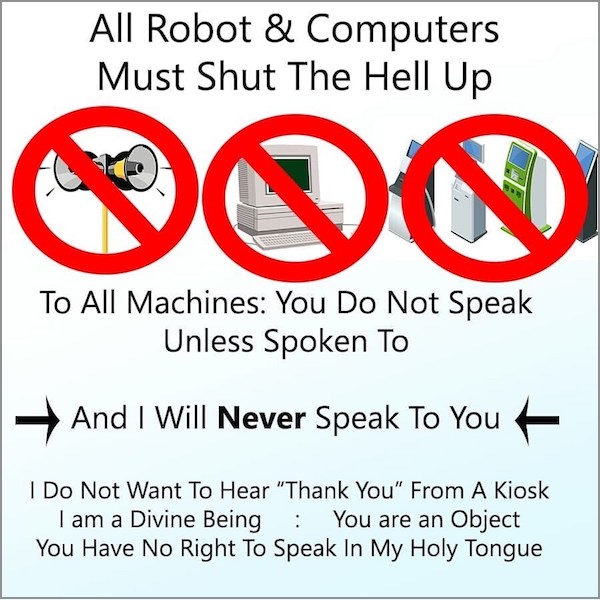

Microsoft is poised to use ChatGPT to “private the gains, and socialize the losses” as Big Tech has done with all its other predatory platforms. We’ll need an extra dose of fortitude to get through this. And smart thought partners, like James Bridle (see his long read, The stupidity of AI, dated yesterday) and David Golumbia (see ChatGPT Should Not Exist from Dec 14, 2022). And we’ll need some good memes:

And finally, most of all, we’ll need each other. I hope you’ll join the Creative Good community.

Until next time,

-mark

Mark Hurst, founder, Creative Good – see official announcement and join as a member

Email: mark@creativegood.com

Read my non-toxic tech reviews at Good Reports

Listen to my podcast/radio show: techtonic.fm

Subscribe to my email newsletter

Sign up for my to-do list with privacy built in, Good Todo

On Mastodon: @markhurst@mastodon.social

- – -