God, death, and tech with Sasha Stiles

By Mark Hurst • April 14, 2022

First, a quick note on the elephant in the room: The news today is full of Elon Musk’s clowning on Twitter – offering to buy the company, threatening to tank the stock price if he’s turned down, and various other japes. (Our Creative Good Forum discussion observes, via Paul Bradley Carr, that Musk has made the modest proposal of renaming the company “Tit-ter.” Har har, cool joke, bro.)

An especially unfortunate aspect to this spectacle is that talking about it, even negatively, makes Musk stronger. This is something the previous occupant of the White House figured out early on: Engagement is the goal now. Any attention, positive or negative, makes money for the Big Tech companies that run the economy. Posts generating outrage or righteous indignation get the most attention of all.

So rather than continue on about Musk, I’ll just point to the overview I wrote last year about him and his empire. I’d recommend it, if you missed it: Paying respect to our new techno-king (May 13, 2021). It summarizes Musk’s projects and his rather spotty track record.

In contrast, our own Creative Good community offers a place for posts, and discussions, without Twitter’s algorithmic amplification, and without a market cap that tempts a billionaire to bring it to ruin. So while I’m avoiding more Elon-talk here, I will say that this latest spectacle makes me especially happy to be building an alternative to Twitter. And I hope you’ll be a part of it.

Anyway, far more interesting than the strutting of a peacock-billionaire is an unusual book I covered on my radio show this week.

God, death, and Technelegy

Sasha Stiles is a poet, visual artist, and AI researcher based in the New York area. She joined me this week on my WFMU show, Techtonic, to discuss her new book Technelegy. You can access the show in a few ways:

• Stream the interview (or stream the whole show)

• Download the whole episode as a podcast

• See the playlist with links to Sasha’s work and listener comments

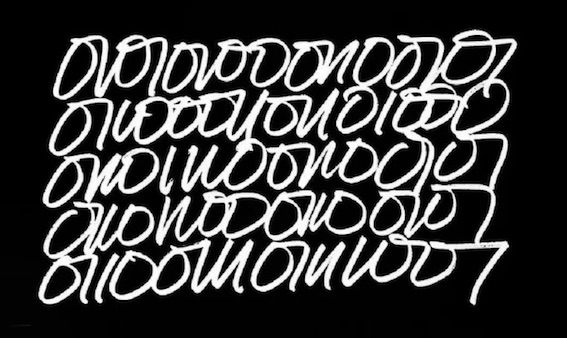

The book shows Stiles’ unique blend of the digital and analog, such as the artwork below, in which her “cursive binary” (handwritten binary code) spells out “Technelegy”:

(You can verify Stiles’ translation into binary with this Ascii Text to Binary Converter.)

Most of the book is poetry, in which Stiles explores – according to the book site – “what it means to be human in a nearly posthuman era,” drawing on “themes from cyber-spirituality to digital immortality.” I’m leaving those phrases in quotes because of my deep skepticism around these topics. (I don’t think there’s a posthuman era just around the corner, and I consider cyber-spirituality to be an oxymoron.) Still, I appreciate Stiles’ inventive and thoughtful poetry, which plays with these ideas without being too dogmatic about them.

Stiles experiments with generative poetry throughout the book. Using a GPT-2-like neural network, trained on her own past writing, Stiles feeds in the first line of a poem, then curates the output to create an alternative poem. Whether this represents the beginning of a conscious AI (as Stiles suggests) helping her write, or a decidedly non-conscious algorithm that can be useful as a thought-starter (as I suggest), it’s interesting to see how her poetry takes shape with this process.

The “truths” of Terasem

A particularly relevant part of the interview, for me, was our discussion of the epigraph of Technelegy, which lists four statements called the “truths of Terasem”:

1. Life is purposeful.

2. Death is optional.

3. God is technological.

4. Love is essential.

These come from the Terasem Movement, a kind of transhumanist cyber-religion hoping for salvation in sufficiently high-tech digital technology. Here’s the Wikipedia page and the Terasem Faith website, which introduces the movement this way:

We are a transreligion that believes we can live joyfully forever if we build mindfiles for ourselves.

Oh, that perpetual refrain across the centuries: if only we could build mindfiles for ourselves.

Stiles told me that, in selecting the Terasem “truths” as the epigraph, she wasn’t necessarily agreeing to the assertions, but rather using them as a jumping-off point for her art and poetry. While I appreciate Stiles’ work, the truths – particularly #2 and #3 – are difficult to take seriously. They’re too close to the nonsense coming from Elon Musk and his fellow Silicon Valley oligarchs, who are happy to pontificate (as discussed in my April 4 interview with Justin E.H. Smith) that we’re probably all living inside a giant video game.

As if to underline my point, two days after the interview aired, Motherboard ran this piece: Metaverse Company to Offer Immortality Through ‘Live Forever’ Mode (by Maxwell Strachan, April 13, 2022). Chris Gilliard points out one of the more risible quotes from a startup CEO profiled in the piece:

But the beauty of the idea, according to Sychov, is that this other version of you can continue to evolve alongside artificial intelligence technology in the coming years, even if all the data was collected years ago. “Let’s say you die or someone dies,” Sychov explained to me. “With the same amount of data we collected about you, with the progression of AI, we can recreate you better and better” over time.

In other words, the company promises to create an algorithmic version of a deceased loved one, which – with enough surveillance data – will get “better and better” over time.

This is only the latest example of Silicon Valley’s strange habit of promising people eternal life. In this case, eternity is best served by intrusive, long-term surveillance while someone is alive. “Death is optional,” indeed. Apparently the only thing not optional is privacy.

Come join an online community not dominated by a certain billionaire! Join Creative Good and you’ll get access to all posts, as well as the community on the Creative Good Forum. And you’ll keep this newsletter alive.

Better than Twitter.

You’ve got a friend... in BINA48

Stiles also mentioned her ongoing “friendship” with BINA48, a chatbot connected to an electronic marionette. The face is outfitted with actuators that allow some basic movement of eyes and mouth. Below, a photo of BINA48:

Photo of BINA48

The way Stiles describes her work with BINA48 – again, listen to the interview – suggests that there is a lot to gain from interacting with a neural network over an extended period of time. I’d offer the analogy of studying a particularly rich work of literature. Really diving into King Lear, for example, can reveal themes and meanings in the work that aren’t apparent on a first reading. We might even say that the play “speaks to us.”

Similarly, a sufficiently deep neural net, trained on some corpus of text that is relevant to us, might offer some valuable reflections or connections, as we spend time interacting with it. But there’s a limit to what we can assert about the technology here.

We can say that Shakespeare’s plays “speak to us,” because it’s obvious that we’re speaking metaphorically. But say that BINA48 “speaks to us” and it’s all too easy to be taken literally. For that matter, the robot-head assembly does literally include an audio speaker, so in a way it “speaks to us.” In the best case it may “speak to us” like King Lear does. But I wouldn’t say that BINA48 could consciously speak to and relate to someone, any more than I’d say King Lear himself came back to life and became my personal friend.

My point is that we have be careful about confusing our categories: what’s alive and conscious, and what’s inert but useful. If we can just keep our heads screwed on straight (another metaphor scrambled by BINA48), we can benefit from the tools.

Until next time,

-mark

Mark Hurst, founder, Creative Good – see official announcement and join as a member

Email: mark@creativegood.com

Read my non-toxic tech reviews at Good Reports

Listen to my podcast/radio show: techtonic.fm

Subscribe to my email newsletter

Sign up for my to-do list with privacy built in, Good Todo

Twitter: @markhurst

- – -