Why I'm losing faith in UX

By Mark Hurst • January 28, 2021

For many years I believed in UX. The so-called "user experience" of a website, app, or other digital product could spell the difference between success and failure. After all, an easy, intuitive, or convenient UX would make the customer's life better, while simultaneously achieving the team's goals - usually, higher profit or lower service costs.

In 1997 I started Creative Good with this belief in UX. And for a number of years, the belief proved to be right. Companies saw a material benefit from making their products better - really, actually, better - for their customers. I'll call that Decade 1, from 1997 to 2007: the golden era of online UX, when companies were willing to invest in listening to customers in order to serve them better. Retail, finance, healthcare, travel, and other sectors all had some interest in improvement.

Things changed in 2008, during the financial crisis, kicking off Decade 2, what I'll call "the slide." Lasting from 2008 to 2018, it was a time of UX teams seeing diminished influence in the organization. There were many factors at play, but a major one was the exodus of financialization experts from Wall Street to Silicon Valley. Suddenly the "get rich quick" mentality that had caused the 2008 crash was being adopted by senior leadership at Big Tech firms. Now it was data and algorithms, not UX, that mattered most. UX was, at best, a superficial sop for users.

I remember a moment in 2014, right in the middle of Decade 2. I was giving a talk on my book Customers Included to a large company in the travel industry. The UX team, charged with managing the digital presence of this travel giant, pulled me aside afterward for a private Q&A. They were not satisfied with my talk: sure, they said, we can do the research, listen to customers, and make recommendations for improvement. But what if leadership not only ignores our recommendations but tells us to do something different? I'll never forget one comment. "We're lying to our users," one anguished UX designer told me, explaining that leadership regularly ordered the UX team to create designs that were intentionally misleading. Apparently it helped boost profits.

I think I responded to the frustrated designer that my book explained the importance of internal politics, as "The Organization" is the last section of the book. But the designer, and the whole UX team, were right to be skeptical. Now in UX's Decade 2, this team was living through the slide: the decline of UX influence in digital organizations. No book, or team workshop, was going to change the power dynamic inside the corporation. UX served, at best, to mitigate the visible harms of data-backed engineering running the show.

I had no idea it was going to get even worse.

Decade 3, starting a few years ago and still very much in force today, is "the redefinition." If the slide in Decade 2 caused the diminishment of UX, Decade 3 transformed UX into an entirely new discipline. I'm speaking generally, with the caveat that of course there are exceptional teams out there still practicing "good UX." But the larger trend in the tech industry today - led more strongly than ever by the Big Tech monstrosities - is an entirely new way of relating to users.

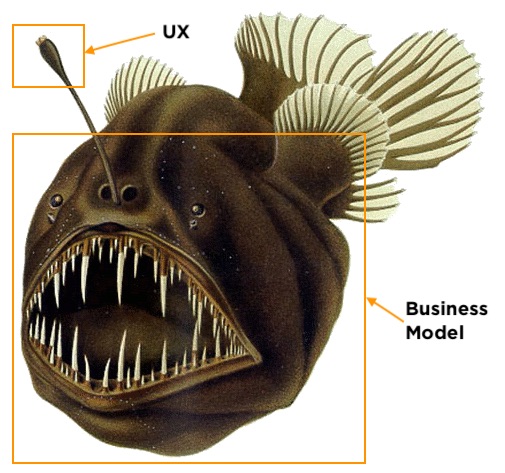

Increasingly, I think UX doesn't live up to its original meaning of "user experience." Instead, much of the discpline today, as it's practiced in Big Tech firms, is better described by a new name.

UX is now "user exploitation."

A perfect example is the Amazon Prime cancellation process. I learned about this from Isabella Kwai's New York Times story two weeks ago: a consumer-rights group in Norway has filed a complaint about Amazon's absurdly difficult, inconvenient process for turning off a Prime subscription. Here's the original complaint, which includes this (emphasis mine):

The cancellation procedure is long, and consists of six separate pages. On each separate page, the consumer is nudged toward keeping their Prime membership, even though they have began a procedure to end the agreement. . . . This uncertainty is further strengthened by having to scroll through the page, which is full of text and graphics to show how cancelling the membership will mean the loss of many benefits.

(There's a video showing the process, too.)

This example may not seem like much: cancellation processes are often a hassle, even in Internet companies. (As far back as 2006, AOL made national news for insolently refusing a customer's cancellation request.) But this is different.

Amazon, we must remember, used to be the leader in UX online. For years - certainly throughout the first decade of online UX - Jeff Bezos made a point in every interview, every press story, of hammering his strategy: customer experience, customer experience, customer experience. Here was a company, Bezos asserted again and again, maniacally dedicated to serving the customer. And it worked: without that singleminded focus early on, there would be no Amazon behemoth today.

But now Amazon has embraced a new kind of UX, as shown by the Amazon Prime cancellation process. What should be a single page with a "Cancel my subscription" link is now a six-page process filled with "dark patterns" - deceptive design tricks known to mislead users - and unnecessary distractions. This isn't an accident. Instead, and this is the point of Decade 3, there's a highly-trained, highly-paid UX organization at Amazon that is actively working to deceive, exploit, and harm their users. UX has completely flipped now, from advocating for the user to actively working against users' interests. To boost profits, UX has turned into user exploitation.

And Amazon is hardly unique. I've written plenty about Facebook, Google, and other tech giants - for example, Calling the culprits by name from last month. But where Amazon leads in UX, the rest of the tech industry generally follows.

And it's not just the Big Tech firms. The academy, led by Stanford University, has provided a philosophical basis for the shift in UX. My column Juul and the corruption of design thinking (Oct 24, 2019) describes how "design thinking," as promoted by Stanford's d.school, has provided crucial rationalization for Silicon Valley's exploitation of human beings. In Juul's case, fraudulent proclamations of "empathy" served as a smokescreen for the true aim of the company, which was to use d.school-inflected product design to addict, capture, and monetize an entire generation of young nicotine users. (Fortunately, the company's star has fallen recently - see my mediadiet syllabus on Juul.)

The cost of exploitation

The unholy rebirth of UX has had a staggering cost. It's well beyond the stupid hassle of Prime cancellations, and even beyond the Big Tech criminality I've written about. In the end, turning UX into an actively harmful discipline has drained talent and expertise away from projects that could, and should, have had more help.

An enraging example comes from right here in New York City: our vaccine websites are impossible to use. From the New York Times: The Maddening Red Tape Facing Older People Who Want the Vaccine (Jan 14). And on Twitter, Hee Jin Kang described a personal experience: "I've been trying to make appts for my parents (both 65+) & the lack of a centralized website is beyond frustrating." (Read Kang's whole thread for a blood-boiling description of the process.) As I posted in response:

In the single biggest public health crisis in the world, New York can't build a usable vaccine website. The telephone - 1950s technology - is our best option, after 25 years of web development. Shameful.

We're headed into a dangerous time, when our society is run on digital platforms, and UX isn't leading the way to ensure that those tools are usable. While the best-trained (and highest-paid) UX professionals are put to work optimizing the exploitation and deception of online users, New Yorkers continue to die from Covid, because there's no easy way to schedule a vaccine visit.

For the few teams that still do want to help their users, and don't have a toxic business model, contact me. I'm still here, and Creative Good is still here, ready to help. I've posted my own worldview, both in A simple tech ethic (July 23, 2020) and in my book Customers Included, but I'm not in the majority. Thanks to Big Tech's corrupting influence, UX is all too often devoted to exploitation.

(via Erika Hall)

Read the next column: No, an exploitative product is not "great" (Feb 4, 2021)

Translations:

• Japanese (ITnews, Feb 1, 2021)

• Chinese (intersection.tw, Feb 9, 2021)

• German (manx.de, Feb 12, 2021)

Other links:

• Novelist Jonathan Lethem was my guest this week on my weekly radio show Techtonic, talking about his new book The Arrest - which describes the world when the screens go dark - though one embodiment of Silicon Valley exploitation remains alive. See playlist, listen to the entire show (you can jump to the interview), or download the podcast.

• Speaking of Techtonic, the anglerfish image above is reminiscent of my 2019 Techtonic t-shirt design, created by Greg Harrison and me. (It's no longer available, but there will be a new Techtonic t-shirt soon, for WFMU supporters - stay tuned.)

• I wrote about the best messaging apps on my site GoodReports.com, a guide to alternatives to exploitative Silicon Valley services. (Whatever you do, don't use WhatsApp or Facebook Messenger.)

• About the GameStop stock's unlikely rise, which is the center of financial news right now: Reddit users are being manipulated to benefit Goldman Sachs and others, Pam Martens writes today. Exploitation is still alive and well on Wall Street.

• If you're new here, read past columns.

Until next time,

- Mark Hurst

Read my non-toxic tech reviews at Good Reports

Listen to my podcast/radio show: techtonic.fm

Subscribe to my email newsletter

Sign up for my to-do list with privacy built in, Good Todo

Email: mark@creativegood.com

Twitter: @markhurst

- - -