How to prove vaccine status – with privacy

By Mark Hurst • August 12, 2021

In New York City, we’ll soon need to show proof of Covid-19 vaccination before we can enter restaurants and other venues. Similar requirements are being adopted around the world, with national and municipal governments alike issuing various types of “vaccine passports” to show proof of Covid-19 vaccination. (As I wrote this column, San Francisco just announced its own vaccine passport requirement.)

At first blush, vaccine proof is such a familiar part of my life that it’s barely worth commenting on. Growing up as the child of a naval officer, I got used to seeing the printed yellow card, the shot record that allowed us entry into whichever European and Asian country we moved to. In recent years, my wife and I have faithfully maintained our son’s shot record, printed on that same yellow card stock, as he’s received the normal childhood vaccinations. The process has always worked well.

But the Covid-19 vaccine is different, since it arrived during the smartphone era, in an economy dominated by surveillance capitalism. The Covid vaccine (which is good!) and proof of vaccination (which worked fine in the past!) are now encountering a complication: most “vaccine passports” are being rolled out as mobile apps. Today’s smartphone apps often suffer from questionable security practices and shady data-sharing arrangements. So I can empathize with people who look at digital vaccine passports with skepticism, even suspicion, with one question in mind:

How can I prove my vaccination status without compromising my privacy?

On the most recent Techtonic, I was happy to speak with Albert Fox Cahn, executive director of the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project, or STOP, to answer that question. Albert is emerging as a go-to expert for journalists writing stories that touch on privacy issues. (For example, see this NBC News article, from August 5, quoting Albert about vaccine passports.)

I’d recommend listening to what Albert said on Techtonic:

• See episode links and listener comments.

• You can also download the entire episode as a podcast.

Having said that, I’m happy to summarize Albert’s answers here, as best I understood them (all errors or omissions are mine, not Albert’s!). I haven’t seen this elsewhere: a simple overview of the main ways to prove vaccine status.

Even if you don't live in New York State, this still applies to you. If and when your city or state (or country, outside the US) launches a vaccine passport, these are downsides to look out for.

Excelsior Pass: downsides

Excelsior Pass is the vaccine passport app issued by New York State, for anyone who got both vaccine shots in-state. Users enter identifying data (birthdate, etc.) and the app finds their vaccine status from a New York State database. Here are the downsides:

1. Availability: The app won’t work for you if you got one or both vaccine shots outside New York State. By itself, this isn’t a big deal, and I’d be enthusiastic if this was the only downside. But there are others.

2. Security: The app isn’t secure, as it’s trivial to spoof another person’s vaccine status. In other words, you can easily log into the app as someone else, using easy-to-find information. In a Daily Beast column (June 3), Albert Fox Cahn writes that it took him eleven minutes to carry this out:

After getting consent from an Excelsior Pass user, I tried to download their pass, logging into their account using nothing more than public information from social media. Eleven minutes after he gave me the greenlight, I had a copy of his blue Excelsior Pass in hand, valid for use until September.

3. Buzzword hype: As covered in this Intercept piece by Sam Biddle (March 24), IBM developed the technology underlying the Excelsior Pass and is now heavily marketing its use of “the blockchain” – one of the most over-used, and under-delivering, buzzwords in recent years. As security consultant Bruce Schneier puts it, “any actual blockchain features” in the app “don’t add anything.” And they might actually introduce further security problems.

4. Privacy: In our Techtonic interview, Albert describes how the Excelsior Pass generates a unique QR code that can be scanned by the restaurant or bar that you visit. Unfortunately, this appears to grant New York State – and any third parties it partners with – to track you, as each QR code-scan generates a location and timestamp. (See also this NYT story (July 26) saying that QR codes allow “tracking, targeting and analytics, raising red flags for privacy experts.”)

5. Habituation: As I pointed out during Techtonic, I remember years ago there was a fad of Foursquare “checkins,” in which Foursquare users would publicly post on social media their arrival at a restaurant or bar. The fad vanished when people realized that they were, indeed, publicly posting their minute-to-minute location. (Ugh.) A state-funded, Big Tech-built app like Excelsior Pass puts us on a slippery slope toward QR-code checkins becoming compulsory: either allow the QR-code scan like a compliant citizen, or get lost. Excelsior Pass and similar apps are habituating citizens to intrusive surveillance. (See more details in The Good, The Bad, & The Invasive, a deep-dive on vaccine apps and privacy from Albert and his team at STOP.)

NYC Covid Safe: downsides

NYC Covid Safe is a vaccine passport app just launched by New York City. (To be clear, this is a totally separate app from the New York State app, Excelsior Pass, described above.) The app asks users to upload images of their photo ID, their vaccination card, and any proof of a negative Covid test result, and then displays green checkmarks for successful entry. Here are the donwsides:

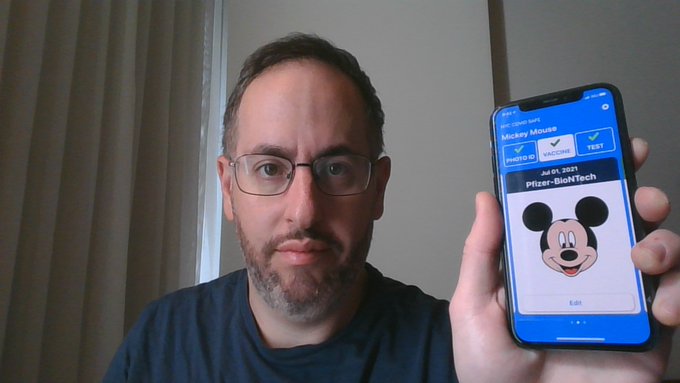

1. Accuracy: As Albert Fox Cahn explained to WNYC News (Aug 1), he was able to get green checkmarks from the app on all three items – photo ID, vaccination card, and Covid test result – by uploading the same image three times. It was an image of Mickey Mouse. Here's Albert with the evidence:

(Source: Albert Fox Cahn)

The glaring lack of accuracy calls the entire app into question. If NYC Covid Safe literally can’t tell the difference between a vaccination card and Mickey Mouse, why would anyone use it? Why would restaurants accept its green check marks? All I can think is that this is a cynical bit of “Covid theater” which will do nothing to foster New Yorkers’ trust in their city government.

2. Lack of functionality: There’s really nothing else to the NYC Covid Safe app. It appears to be an overblown camera app – just generating green checkmarks for any uploaded image. As Albert pointed out on Techtonic, it’s not clear why the app would even be called a Covid-related app, as its functionality appears to have nothing whatsoever to do with Covid vaccination.

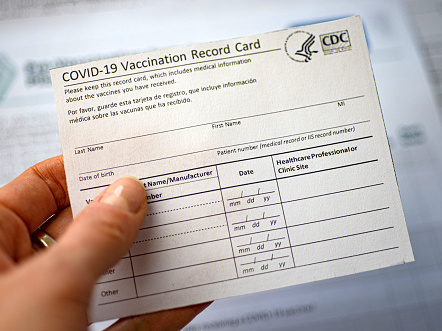

CDC vaccination card: pros and cons

Since the vaccine apps from New York State and New York City both have fundamental problems, we’re left with one final way to prove vaccination status: the white printed card issued by the CDC.

First, the downsides:

1. It’s too big for your wallet. As the Atlantic puts it, The Vaccine Cards Are the Wrong Size (August 10).

2. The paper could get frayed or ripped if you carry it around.

3. Vaccine cards can be forged.

On the other hand, as a piece of paper, it doesn’t require a smartphone – and it doesn’t generate a trail of digital data, shared with state and corporate partners, leaving you vulnerable to surveillance. And that's why the CDC card is the basis of the solution.

Here’s what Albert recommended on Techtonic as the best way to prove vaccine status, while retaining privacy:

Photocopy your vaccine card, shrinking it to wallet size, and then laminate it.

It’s important to laminate the copy, not the original vaccine card itself, since there may be booster shots that require more written entries added to the card. (This solution still works: if you get a booster shot, you would just need to make a new photocopy of the card and laminate it.) In any event, with this laminated card, you’ll always have proof of vaccine status – right next to your other proof of ID: your driver’s license. It turns out that the idea of a printed and laminated ID card is reliable, familiar, and decades old.

And you can leave your smartphone at home.

And now, a special treat. Last week, after I mentioned that just over 1% of newsletter subscribers have joined Creative Good, a few more people became members. (You can help bring it up to 2% – by joining here.)

To celebrate our new arrivals, I give you:

Three memes about processing 2020.

Post a comment (for Creative Good members)

Forum posts for Creative Good members

Below are Forum posts only for Creative Good members: you can join Creative Good to get access.• 🔒 Notable articles about China (new thread posted today, August 12).

• 🔒 Artists, mistreated by YouTube, reveal the risks of working with Google (August 10).

• 🔒 Links about QR-code privacy and Apple's photo-scanning announcement (August 10).

• 🔒 Discussing a new alternative to Google Search (July 30).

• 🔒 Things that are not a computer: brains, cities, and churches (July 29).

Click here to join Creative Good.

Until next time,

-mark

Mark Hurst, founder, Creative Good – see official announcement and join as a member

Email: mark@creativegood.com

Read my non-toxic tech reviews at Good Reports

Listen to my podcast/radio show: techtonic.fm

Subscribe to my email newsletter

Sign up for my to-do list with privacy built in, Good Todo

Twitter: @markhurst

- – -