Amazon Ring is creating the surveillance complex

By Mark Hurst • February 25, 2021

Amazon has launched an updated version of its Ring video doorbell, as reported in The Verge (Feb 24). With "a taller field of view and enhanced motion detection capabilities," this new camera can see a lot more from its perch at the front door, including head-to-toe images of whoever walks past. Gaze upon this new innovation, as it certainly gazes back at you:

To the Verge's credit, one sentence of its otherwise fawning review does mention that Ring has "been criticized for its privacy policies and police partnerships over the past few years." What the Verge does not mention is the major news story from a few days earlier, surely known to the Verge editors, that apparently was too negative to bring up. What happened is that police in Los Angeles asked Amazon to help access surveillance video from nearby residents' Ring doorbells. To spy on Black Lives Matter protesters.

A Feb 16 story by Sam Biddle in the Intercept quotes emails, obtained by the EFF, showing the LAPD asking Amazon for help in obtaining protest footage from homeowners' cameras. Amazon has provided close support to the LAPD over the years, going so far as providing email templates for the LAPD to send out to homeowners, nudging them to share their Ring's video with the police (see this Motherboard article). Amazon already has access to the video, since - for many homeowners - Ring footage is automatically uploaded to Amazon servers.

To understand why this is such a problem, consider the counterpoint. I imagine think tanks funded by Big Tech (plenty of them exist) would come to Amazon's defense by saying something like: "You're overreacting. All the police asked for was footage of a few protesters, and only where there was evidence of violence. Let's say 99% of the protesters were peaceful: Why is it bad to ask for an excerpt of footage of just a few who broke some windows?"

This is a clever defense, relying on sleight-of-hand to frame the question around cameras, as though it's the very idea of recording footage that is under debate. ("What do you want to do, ban all cameras? That horse is out of the barn," and so on.) Let's be clear: The problem isn't with cameras per se, nor the desire for security. Mom-and-pop stores have used security cameras for decades, capturing (say) a 12-hour window of footage before it's then recorded over, or otherwise wiped, the following day. If there's a break-in, the store owners can choose to share the footage with the police. This decentralized and limited use of surveillance technology provides security, and a tool for law enforcement when necessary, but within strict boundaries, so that it doesn't turn monstrous for the rest of us.

What happens with Ring doorbells, in contrast, is that the cameras are always on, the footage never gets deleted, and it's shared with the police and the world's most powerful corporation, in perpetuity, for whatever use the company desires. (Amazon would of course respond that they're shocked! anyone who suspect them of surveillance, that footage is never shared without users' consent, and so on. Ignore the PR act and look at their behavior in LA. For that matter, look at how Amazon was caught stealing tips from its drivers.)

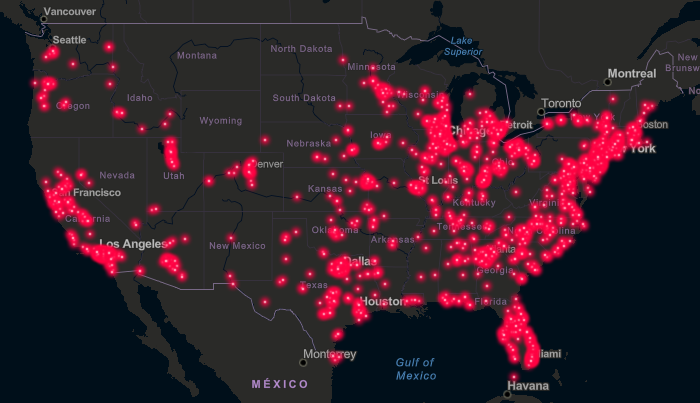

What's more, Amazon is not just accessing video from an occasional device. This is a national network of millions of surveillance cameras, centralizing all the data within Amazon for its own opaque use. Courtesy the EFF, here's a map of the roughly 2,000 law-enforcement partnerships with Amazon Ring:

Source: EFF

Amazon is building the infrastructure to watch all of us, all the time, from every front porch in America, and to store the video data forever, for arbitrary analysis and feedback via opaque algorithms, and with a handy partnership with local law enforcement, just in case the police may want to draw on it - ever - for any reason - whether the citizens are told about it or not. (Indeed, the EFF reports that the LAPD was cagey about why they wanted the protest footage in the first place.)

Among other effects of Amazon Ring, we're likely to see a chilling effect on lawful protests. As the EFF puts it, "People are less likely to exercise their right to political speech, protest, and assembly if they know that police can acquire and retain footage of them." I'd argue that it's even worse than that, since the footage is also being acquired by Big Tech. After all, Amazon has a lot more power than the local police department, and the company's activities are totally unaccountable to the democratic process.

But even for people who don't foresee joining a protest, this should be equally concerning. The day-to-day experience of living under the ubiquitous gaze of cameras is not good for anyone. Arthur Holland Michel knows all about this. He's the author of Eyes in the Sky: The Secret Rise of Gorgon Stare and How It Will Watch Us All, a book about aerial surveillance cameras that were first launched over the battlefield in Afghanistan, and now are being deployed against American citizens in the skies over our own cities.

I spoke with Arthur on my radio show Techtonic back in 2019 about whether this sort of surveillance generates a safer, healthier society. You can click here to listen to his response, but here's what he said:

In a way, I do want to live in a society where violent criminals think twice before committing a murder. Because they know that they might be in the crosshairs of some aerial surveillance system. I think that would be a pretty positive thing. In fact, to take that even a step further, if we have a capability to make people think twice before committing heinous crimes, we sort of have a responsibility to use that capability.

But there's a flip side. And the flip side is ... that this is an equal opportunity form of surveillance, in terms of, it is going to give everybody second thoughts about their actions. Nobody believes that they have absolutely nothing to hide. Nobody wants to be followed, persistently, twenty-four seven, wherever they go.

So the question is, is that just the tradeoff of having more safety? Do we have to necessarily give up that freedom and privacy in the name of security? Or, is there some way to find a balance? And it's a question that people have been asking for centuries, but one that I think has taken much greater urgency in recent years, because we really are living at an unprecedented time in terms of the emergence of new surveillance technologies. Particularly wide-area surveillance technologies, and also automation. And I feel like time is running out to start answering those questions.

(That was from Techtonic, September 9, 2019. Here's the episode page with links and notes.)

The surveillance complex

What do you call it when ordinary citizens are enlisted in installing digital spy devices, for use by the state, with data also flowing back to a megacorporation for opaque analysis? We might call it the "surveillance state," though that doesn't quite grasp the scope. The Stasi in East Germany, for example, ran a particularly cruel and effective system of spying and repression, practically the definition of a surveillance state. But that was just the state. Amazon, with its Ring doorbells, is creating something new:

• A larger domain, joining a corporate partner with state power, with

• wider reach, as digital tools allow scalable, totalized surveillance, and

• greater power, as Amazon operates under the protection of legal defenses like NDAs, trade secrets, and the like - not to mention its essentially unlimited supply of money.

I'd like to propose that instead of the surveillance state, we should call it the surveillance complex, an echo of the "military-industrial complex" that President Eisenhower warned against in his 1961 farewell address. Today's surveillance complex is similarly a partnership between state power (the LAPD, in the example above) and unaccountable corporate power (Amazon, though just as often it's other Big Tech companies). The system is a multi-headed beast, a kind of hyper-hydra, and the Amazon Ring surveillance doorbell is just the visible end of one of the tentacles.

One final pointer, if you'd like to dig just a little deeper: This is not the first digital surveillance state we've built. What's growing now in the U.S., with Amazon Ring, and Palantir, and home-spying devices from Facebook and Google and subsidiaries - Fitbit is now a Google surveillance product - it's just a petri dish of devices and data streams and networks, all spying on us, all the time. But it's not new. Instead it's an iteration, a version 2, of something we built a few years ago, in Afghanistan.

If you don't know about this already, I have a crazy story to tell you. Totally true, but crazy. I covered it on Techtonic this week with my guest Annie Jacobsen, author of First Platoon: A Story of Modern War in the Age of Identity Dominance. (Click here to listen to the interview, or see the episode page.)

A summary. Back in 2012, the U.S. Army's official strategy in Afghanistan was total surveillance: getting the fingerprints, facial images, iris scans, and other biometrics from, well, everyone. I mean every - single - Afghan - citizen that Americans encountered. The goal was biometric capture of 80% of the entire Afghan population.

As much as Americans (rightly) condemn the Chinese government for the surveillance state being built to oppress Uighurs in the western region of China, Americans built a surveillance state in Afghanistan with largely the same goals. And then there was the, frankly, bananas story of what happened with First Platoon. (Again, take a listen.)

Jacobsen writes this near the end of her book (p. 292):

America is becoming a society overwatched by a digital-genetic panopticon. What legal scholars describe as "a burgeoning National Surveillance State." There are more than 85 million ground-based surveillance cameras installed across America, the largest per capita share of surveillance devices globally, with more than one surveillance camera for every four people.

I don't think I'm spoiling the book to tell you that our surveillance state in Afghanistan did not, in the end, solve the conflict. Afghanistan is not a happier, healthier, or more secure place after we installed our total surveillance system. (On the flip side, a few tech executives and military contractors made a lot of money. So there's that.)

Here's the question, and let's really rack our brains here: What do we think is going to happen as we install the same system here in the US?

What path are we on, when Amazon Ring devices spy on BLM protesters? Is this the country we want to build? Is this the world we want to leave to the next generation? My suggestion: Let's think, hard, about what we'd like to do next. Time available, I may have some suggestions next week. Stay tuned.

(By the incomparable Tom Gauld for New Scientist)

By the way, if you'd like to go even further on this topic, you have to understand the role of Palantir, Peter Thiel's surveillance company, which is working with military contractors, and police departments like the LAPD, which in turn is working with Amazon Ring. I strongly recommend listening to my interview with Prof. Sarah Brayne, author of Predict and Surveil: Data, Discretion, and the Future of Policing, from last month. Listen to the interview or see the episode page.

All of the interviews above are also on the Techtonic podcast.

If you're new here, read past columns. (You can also get them via the email newsletter.)

Until next time,

- Mark Hurst

Read my non-toxic tech reviews at Good Reports

Listen to my podcast/radio show: techtonic.fm

Subscribe to my email newsletter

Sign up for my to-do list with privacy built in, Good Todo

Email: mark@creativegood.com

Twitter: @markhurst

- - -