Juul and the corruption of design thinking

By Mark Hurst • October 24, 2019

I've never been a particular fan of movie villains, the "bad guys we love to hate" sort of characters. But whenever they make the film about Juul, I'll grab the popcorn. The company's lack of a moral compass, its shameless commitment to growth at any cost, and its skill in marketing an addictive product, all make Juul a perfect movie monster. And there's a twist, too, which I'll get to.

Source: Stanford's Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising (SRITA)

Juul dominates the vaping industry. The San Francisco-based company followed the Silicon Valley playbook with wild success, achieving explosive growth by aggressively marketing its addictive nicotine devices to underage users on social media. The result: Juul is now the favorite vaping brand of American high school students, as reported by Jia Tolentino in the New Yorker (May 2018). More recently, according to a WSJ article last month, "nearly 28% of high school students this year said they had used an e-cigarette at least once in the past 30 days." This from a brand that was practically unknown a few years ago!

Late last year the two Juul co-founders sold about a third of the company to Altria, the tobacco giant and maker of Marlboro cigarettes, making the co-founders instant billionaires. The combination of an addictive product, persistent social media outreach, and a lucrative investment from the tobacco industry yielded the Silicon Valley dream: insane, near-overnight riches.

Juul's fortunes have shifted somewhat in the past couple of months, though, as regulators have finally arrived. There are now multiple investigations into Juul's marketing practices and the harmful effects - especially on underage users - of inhaling pure nicotine and flavor chemicals. News of a "mystery illness" afflicting e-cigarette users has gained a lot of attention, and now several states have launched lawsuits or outright bans of Juul and other vaping products. (See news from New York, Massachusetts, Maryland, and North Carolina. There's also a federal criminal probe as the US considers a nationwide ban. More in this news roundup from the WSJ.) As a result, the Juul CEO was forced out, though the two billionaire co-founders have comfortably maintained their positions.

I'm fascinated by Juul. As an advisor to product teams, I'm always interested in the underlying approach that guides product decisions. Juul's case study comes with a twist: its design philosophy is a corruption of my own.

Design thinking and Juul

An old joke says that only the software industry and drug dealers call their customers "users," and for Juul this is doubly apt, as it's a Silicon Valley company that literally is a drug dealer. Juul has drawn on best practices both in digital user experience (designing an attractive, easy-to-use product) and drug-dealing (addicting users, and keeping them addicted, for as long as possible). This approach was not a lucky accident but an explicit decision on the part of Juul's founders.

A few years before becoming a billionaire, Juul co-founder James Monsees gave a 2013 TEDx talk in Brussels. Though he rambles through much of the talk, in one section Monsees reveals a key insight (emphasis mine):

A few years ago, I had the privilege of being a fellow at a place called the d.school on Stanford's campus. We did something very simple there. We taught a concept called design thinking. And design thinking is purely just empathy. You try to understand a person's needs. And then you test and see if you got it right by creating prototypes.

I think it's fair for Monsees to credit Stanford and its "design thinking" curriculum for Juul's design philosophy. After all, Stanford - whether through its Persuasive Technology Lab, or the d.school as in Juul's case - taught any number of Silicon Valley startup founders to employ dark patterns and addiction loops in service of a "growth at any cost" mindset. Of course, Stanford also contains groups working towards better ends - for example, SRITA's research on tobacco advertising - but Monsees' comment is a reminder that Stanford's tech-friendly courses have given rise to some truly toxic companies.

Where I differ with Monsees is his assertion that his approach is "just empathy." I'm not sure it's quite accurate to say "empathy" drove Juul's push to addict millions of high school students to its device. Whatever one might think of the popular "design thinking" method (good in theory, watered down in practice? a topic for another column), Juul certainly represents a corruption of the ideal. Design thinking, as Monsees understood it from Stanford's d.school, granted him enough "empathy" to prototype a device that creates and maintains addictive behavior.

Juul and empathy

In contrast, a better design method - which I call Customers Included in my book of the same name - should be based on empathy, which means swearing off deceptive marketing and addictive products. Empathy means acting in the long-term best interests of the customer and their community, and here that would mean trying, even if gradually, to release the user from their nicotine addiction.

Juul occasionally claims to be working on "smoking cessation," saying their devices are solely meant to help smokers quit cigarettes (and use Juul instead). This of course means replacing one addiction with another, but Juul claims its vaping products are less harmful than cigarettes. I'll admit to some skepticism around any health claims from a company marketing an addictive device to teenage Instagram users. But here again James Monsees is available to clarify Juul's position. From his TEDx talk:

Tobacco companies aren't the only groups that have been trying to innovate in this space. So think about pharmaceutical companies. We've got nicotine gum, and lozenges, and the patch, and even cream that you put on your hands that has nicotine in it. But none of these things are even addressing the core consumer need. These are products designed for abstinence. They're trying to get us, to allow us, to stop doing something that inherently we love to some degree. And that's a problem. Because the idea that you can prescribe a solution to a desirable good is wrong. The idea that prescription is somehow gonna lead to desire is totally false. Prescription doesn't lead to desire, and desire is the heart of a luxury good or experience.

In other words, Monsees is telling us, don't bother with abstinence. There's no use in trying to get people to stop smoking - because the very idea is "wrong." It's clear that smoking cessation was never Juul's goal, beyond opening up a market for its own devices. Instead, Monsees intended from the beginning to give people something they'll "love": a product that meets the "core consumer need" to stay addicted.

In the end, Juul chooses to see the customer's addiction as one more consumer desire to be fulfilled by a product. And if the customer isn't addicted to nicotine (as most high schoolers encountering Juul aren't yet), Juul sees an opportunity to create an addiction that it can then feed. Lacking any semblance of empathy, Juul doesn't just fall short of "customers included." It's actually the opposite.

Juul and Congress

This past July, Monsees was brought in front of a Congressional committee to answer to charges that Juul had run social media campaigns targeting underage users. The hearing included a fascinating exchange between Monsees and Representative Katie Hill of California, who asked Monsees about Juul's investment in "influencer campaigns." (Video.)

Hill opens by reminding Monsees that the committee had asked for "every celebrity, influencer, and marketing agency" that was engaged by Juul. In its response, Juul claimed only four influencers and stated, in writing, that they "do not have a traditional celebrity or influencer program." When Hill asks about this, Monsees agrees that he stands by that statement.

Hill then refers to a Juul document describing a "Juul launch influencer seeding program" with a goal of identifying 280 influencers in Los Angeles and New York "to seed Juul product over three months." Does Monsees still maintain that Juul didn't have an influencer program? Monsees plays dumb: "I'm sorry, I don't have a copy of that document... There were a lot of documents we provided." But Hill won't let up. She brings up another Juul document asking a contractor to find "social media buzz makers with a minimum of 30,000 followers" and to develop "influencer engagement efforts, to establish a network of creatives to leverage as loyalists for Juul."

Monsees tries to derail Hill with the smoking-cessation defense: "Of the billion smokers globally, 70% want to quit" - but Hill cuts him off and hammers out numbers from yet more Juul documents: "200 casted influencers"... "280 Juul influencers from Grit"... "a target to build 1,000 Juul influencers"... "12,500 influencers introducing Juul to 1.5 million people"... "29,000 influencers"... and a May 2018 document titled, damningly, "Juul Influencer Program."

Hill asks: "Do you still maintain you didn't have an influencer program?"

Monsees: "To the best of my knowledge, um, we- I'm sorry, are you talking about a paid influencer program, is that what we're discussing here?"

This is the point I laughed out loud while watching the video. Hill has thoroughly roasted Monsees, and he responds with a cringe-worthy performance of playing dumb that, really, looked like a scene from The Office.

Hill responds: "No, we're talking an influencer program. But you're on the record and you said, a moment ago, that you did not have a traditional celebrity or influencer program. Do you want to maintain that?"

Monsees plays dumb one last time: "Look, uh, it sounds like we're getting into territory I'm not completely familiar with..."

Hill is out of time, so she concludes: "When kids learn about a dangerous project from influencers on social media, it avoids public detection by parents, especially when many of these social media sites are used by millions of kids under 18, which could help explain how Juul got its product into the hands of 20% of high schoolers before parents had even heard of Juul, let alone had a chance to step in."

The whole exchange is fascinating. I'd like to express my thanks to Rep. Hill for allowing James Monsees to publicly display the values (or lack thereof) that guide his company.

And I haven't even gotten to other amusing parts of the hearings, such as the questioning by committee chairman Rep. Raja Krishnamoorthi (video), when...

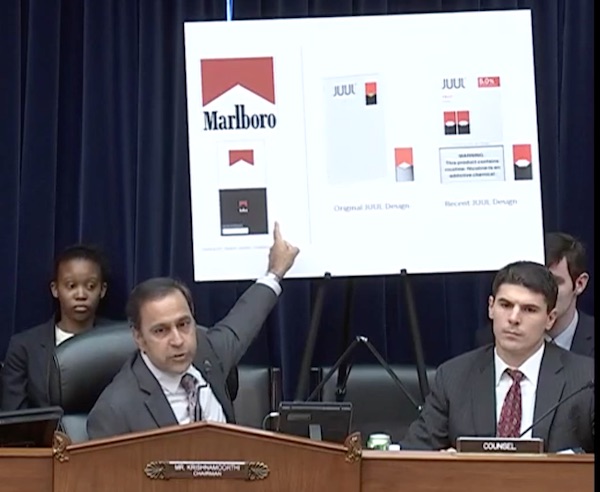

• Monsees denies that Juul's original chevron-shaped design bears any resemblance to Marlboro's world-famous chevron-shaped design. (This despite Philip Morris suing Juul over this very issue in 2016, leading to a settlement in which Juul slightly changed its design, shown below.)

• A moment later Monsees states, emphatically, "The last thing we wanted was to be confused with any major tobacco company." (This despite Juul being owned in part by a major tobacco company, the very company that made Monsees a billionaire.)

Juul isn't the only Silicon Valley company to be based on a corrupt approach to "design thinking," and it likely won't be the last. But it's worth studying, so that - for teams that want to embrace the "customers included" approach - we can steer away from Juul's toxic methods. If we're really lucky, we might even be able to create wider change in the tech industry. But it won't happen by itself. Today Juul is still in business, Monsees and his co-founder are still running the company, and teenagers are still getting addicted.

Keep in touch: subscribe to my Techtonic podcast and my email newsletter, or email me.

- - -

Images:

Below, chairman Raja Krishnamoorthi points out Marlboro and Juul branding. James Monsees apparently can't see any similarities.

More Juul resources:

• My Techtonic radio show, Sept 30, 2019: Starting at the 24-minute mark, I talk about Juul and play the audio of James Monsees at the Congressional hearings.

• List of links for the radio show (Sep 30): this has a Juul in the news section with links to several more recent articles.

Congressional hearings:

The Congressional hearings on Juul were conducted over two days - July 24 and 25, 2019 - with James Monsees testifying on the second day. Details below.

• Part 1 of House Committee on Oversight and Reform: Economic and Consumer Policy subcommittee: "Examining JUUL's Role in the Youth Nicotine Epidemic" (July 24, 2019): details and video, chaired by Representative Raja Krishnamoorthi (IL). Featuring Meredith Berkman, Co-founder, Parents Against Vaping E-cigarettes; Dr. Robert Jackler, Professor, Stanford; Dr. Raymond Niaura, College of Global Public Health, NYU; Rae O'Leary, Public Health Analyst, Missouri Breaks Industries Research; Dr. Jonathan Winickoff, Member, American Academy of Pediatrics; and Senator Dick Durbin (IL).

• Part 2 of House Committee on Oversight and Reform: Economic and Consumer Policy subcommittee: "Examining JUUL's Role in the Youth Nicotine Epidemic" (July 25, 2019): details and video featuring Ashley Gould, Chief Administration Officer, JUUL Labs; Matthew Myers, President, Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids; and James Monsees, Co-founder and Chief Product Officer, JUUL Labs.

• Review of the hearings: Juul Funded High Schools, Recruited Social Media Influencers To Reach Youth, House Panel Charges (Forbes, July 25): "Throughout the hearing, Monsees and Gould maintained that Juul never targeted youth and attempted to distance the company from the tobacco industry. 'Put simply, Juul Labs isn't Big Tobacco,' said Monsees, who is also chief product officer. Monsees, alongside co-founder Adam Bowen, became a billionaire in December after tobacco giant Altria acquired a 35% stake in the company to bump its valuation to $38 billion. Forbes estimates his net worth to be $1.1 billion."

Takeaways, according to the House committee website:

• JUUL targeted schools, downplayed the health impacts and encouraged students to use their products. Meredith Berkman, co-founder of Parents Against Vaping E-cigarettes, testified with two young people that JUUL repeatedly called their product "totally safe," demonstrated how the product worked, and recommended that a nicotine- addicted student use JUUL during a presentation to their 9th grade class, without teachers or parents present.

• Rae O'Leary, of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, testified that JUUL targeted Native American tribes to use as "guinea pigs." In exchange for a $600,000 investment, JUUL solicited tribal medical professionals to provide their devices to tribal members for free and collect information on the tribal members.

• JUUL is replicating marketing tactics formerly used by Big Tobacco. Dr. Robert Jackler, Stanford University School of Medicine, testified about his conversations with JUUL co-founder James Monsees, who said the use of Stanford's tobacco advertising database was "very helpful as they designed JUUL's advertising."

- - -

SHARE THIS:

To share this post, retweet this, or copy and paste this:

Juul and the corruption of design thinking, by @markhurst:

https://creativegood.com/blog/19/juul-corruption-design-thinking.html

- - -